Grammatical Genders: Their History and Future

Medical Pharmaceutical Translations • Sep 30, 2019 12:00:00 AM

Anyone who has tried learning a language other than English has come across different grammatical gender rules. Take German. German can be tricky to learn with its three genders, especially when you use certain homonyms. The German articles die, der and das indicate feminine, masculine and neuter nouns. For example, look at the word “band.” There is die Band (the band, or musical group), der Band (the volume of a book), and das Band (the ribbon). When it comes to writing or speaking, be careful with your genders so that you don't wind up reading a musical group, cutting a volume of a book, or listening to a ribbon.

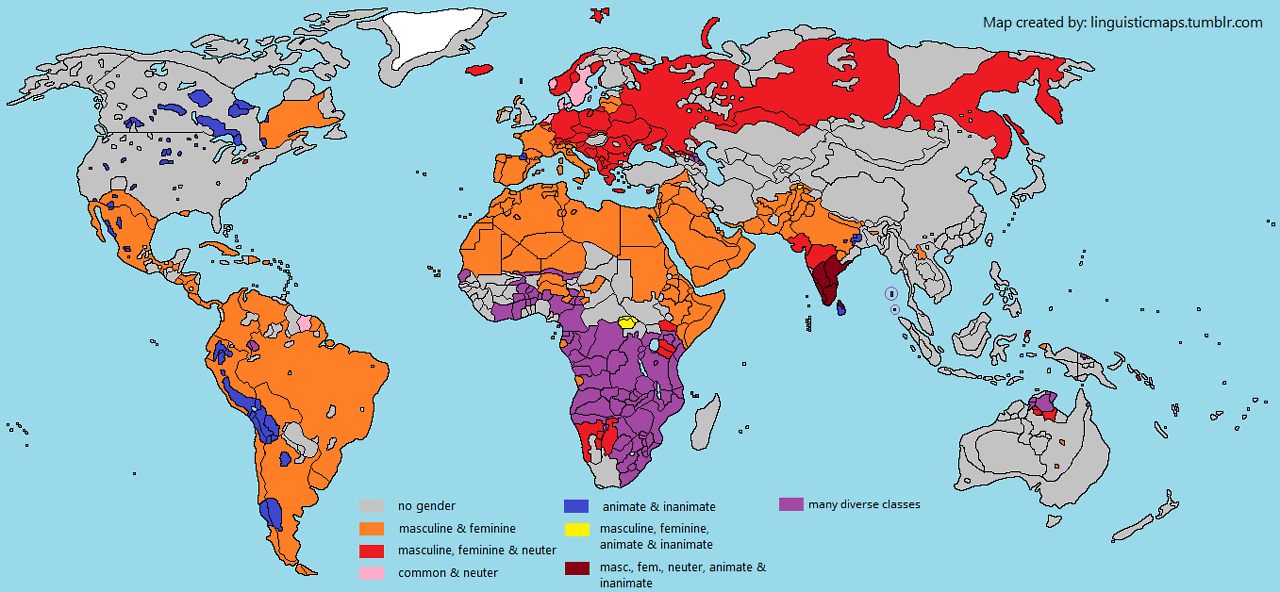

While using many genders in everyday language may seem normal to German or French speakers, it can seem certainty bizarre to many other cultures with language that do not use them. Yet, every language has its own approach to gender. And across the languages of the world, gender systems vary widely. But why do languages even have them? Are they useful? Should they be nixed from our vernacular? Here we discuss the somewhat murky history, evolution and the future surrounding grammatical genders.

Let’s get historical.

So why do we even have genders in languages? Well you can blame-in part-the Roman Empire. The Romance languages (French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian) can all be traced back to Latin, the language of the Roman Empire. Some say that these languages took the place of the now-defunct Latin language. Even German history began with their speakers’ first contact with the Romans in the 1st century BC. Many believe three genders stem from the Proto-Indo-European languages of which German is a part. Other languages with three genders, including most Slavic languages, Latin, Sanskrit, Ancient and Modern Greek.

However, many languages reduced the number of genders to just the masculine and feminine, such as most Romance languages and Celtic languages. Others, like Swedish and Danish, merged the feminine and the masculine into a common gender. English has all lost grammatical gender with the exception of its pronouns “he”, “she” and “it”. Finally, Basque, Estonian, Turkish, and to an extent Mandarin, all completely ignore gender.

According to linguists such as Antoine Meillet, the animate/inanimate distinction preceded the masculine/feminine. Some linguists believe this was typical of a time when rituals and beliefs were attached to natural elements. Over time, language evolved just as monotheistic religions were replacing animistic beliefs, and the masculine and feminine started replacing the animate and inanimate. Meillet believed the animate/inanimate was used simply because it was more useful. He cites as proof that we cannot derive the gender of a word from its “real” characteristics. Why, for example, is a key masculine in German (der Schlüssel) but feminine in French (la clé)?

Let’s blame culture and look to the future.

So perhaps grammatical gender rules were born from-and evolved through-many factors. It really is an interwoven story of historical evolution and culture. And these may hold the key to the future of grammatical genders.

Some linguists refuse to see our experience of the world reflected in grammatical gender. It can be useful for specifying a situation, but often not in a general context. Here is where those genderless languages hold the secret to solving gender-related issues that creep up. The Finnish just a “male, female, man, woman” to the noun whenever necessary.

Or perhaps today’s modern society can benefit from a more Swedish approach to language. Here is an example of a culture intervening to fix a language issue. To keep up with social norms in the 1960s, the Swedes introduced the neutral personal pronoun “hen” as an alternative to “he” and “she.” Overtime, it gained popularity and could be heard in everyday vernacular, on radio and television. This seems like a possible solution in today’s world. Perhaps we really do need, as some have suggested, a new pronoun for instances where we needn’t mention a person’s gender or for non-binary people. A pronoun such as “hen” may break languages out of their antiquated view of the world? Even in the US, they have been using “they” to help along these lines.

Regardless of their history, our languages (and the genders they use or don’t use), shape our view of the world. So, agreeing to reconsider ideological values of our use of gender seems inevitable and just the right thing to do.

Ilona Knudson