Language Influences How We Think: Fact, or (Science) Fiction?

Medical Pharmaceutical Translations • Jun 30, 2017 12:00:00 AM

Sci-fi movies often require viewers to suspend at least some belief. Certain linguists and language lovers had to do this in a very unexpected way when watching 2017 Oscar Best Picture nominee “Arrival”.

A major idea in the film is that the language you speak influences how you perceive reality. This isn’t an original concept from the screenwriter or the short story the film is based on; it’s known as linguistic relativity, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, or Whorfianism.

Some studies seem to support the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Take, for example, this recent experiment, which gives credence to “Arrival” ’s view of language. Testing a group of Swedish monolinguals, a group of Spanish monolinguals, and a group of Swedish-Spanish bilinguals, researchers found evidence that monolinguals perceive time based on the quantifiers used in their language (distance for the Swedish speakers; size for the Spanish speakers). But members of the bilingual group were able to switch and look at time in either way, much like the film’s protagonist.

This doesn’t mean the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has been definitively proven. In fact, there’s just as much research that shows significant flaws in the idea of linguistic relativity.

Here’s one example: One of hypothesis’s namesakes, respected mid-century linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf, claimed that the Hopi language has no precise way of referring to time, and thus the Hopi people don’t perceive time the same way speakers of European languages do. But numerous scholars (and Hopi speakers) have disproven this. Linguistics graduate student Brian Collins gives an amazingly thorough explanation of where Whorf went wrong in this fascinating Quora thread.

Among the most famous present-day anti-Whorfians is John H. McWhorter, author of the book The Language Hoax: Why the World Looks the Same in Any Language. McWhorter sees linguistic relativity as dangerous: Believe that language automatically determines how a people see the world, and you condemn them to simply being stereotypes, and a collective, not individuals.

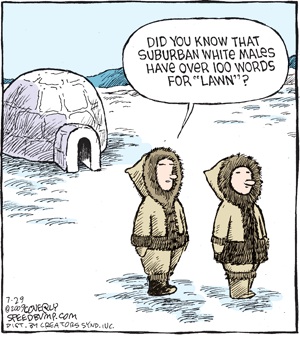

Many other scholars reject the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, as well, and a number of other studies seem to disprove it. So does some strong empirical evidence. Anti-Whorfians are fond of pointing out that if Whorfianism were true, translation would be impossible, since speakers of different languages couldn’t agree on or understand each other. And yet, we can find common ground in translated works of all sort, from Ancient Roman graffiti, to 19 th century French novels, to modern-day Japanese manga or Hollywood movies. Another issue linguistic relativity would call into question would be bilingual- or multilingual-ism.

Consider again the results of that experiment involving language and the perception of time. Languages may describe time differently, but then again, are they particularly restrictive about that? If a Spanish poet, say, described time as “long” instead of “big”, would other Spanish-speakers be completely incapable of understanding this? Whether you consider time in terms of size or duration, you still know the frustration of waiting in line for an hour.

The accuracy of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis isn’t necessarily a “yes” or “no” question. Over time, the hypothesis has been broken down into two different forms. The first, often referred to as “strong” Whorfianism, is the one this blog post – and the movie “Arrival” – mainly refer to. The latter, often called “weak” Whorfianism, suggests that the language you speak might have some influence on your mental abilities and perception, but is not the only or absolute factor.

Wherever you stand on the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, it’s easy to understand how it can inspire stories and films. The concept makes for a fascinating topic of conversation and reflection about how we speak, who we are, and how we experience the universe.

#whorfianism #translations #foreignlanguage #linguisticrelativity #aiatranslations #sapirwhorfhypothesis